Stretching is quite an emotive topic, with many people having strong opinions about its utility, or not! The development of evidence over time and its contextualisation within different settings has meant there’s been quite a bit of discussion over the years whether stretching has a place in training, and perhaps even in rehab. In this post we’re going to answer the question, does stretching impair strength and power – essentially what are the acute effects of stretching and how might this influence performance and or rehab. Given the depth and breadth of this topic, next time we’ll look at the longer term effects of stretching, i.e. stretch training.

The Different Types of Stretching

Okay probably the first thing to clear up is that there are several different types of stretching, usually these are distilled down to 3 classifications:

- Static (adopt a position and hold it with another part of the body)

- PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, involving max muscle contraction at end range then stretch further)

- Ballistic (using the momentum of a moving limb to extend it beyond its normal range)

However, other sub-categories do exist like isometric, passive etc etc. For the purpose of this article we’re going to focus mainly on the effects of static stretching, partially because it’s often the most emotive, and partially because we could classify other types of stretching as something else – like end-range loading. Don’t worry though, we will address the pertinent differences where important.

Reasons to Stretch

Why do we stretch or advocate stretching? Well mainly it’s to increase range of motion (ROM). This could be with a performance goal in mind or indeed where ‘normal’ (and I hasten to say normal) ROM has been limited through injury, surgery etc. and stretching is a restorative intervention. The latter requires a period of training to effect a lasting change and as such we’ll cover that next time. The former might also be performed as a part of a warm-up routine, and in an attempt to enhance performance.

Acute Effects of Stretching

So we take a joint to its end range and hold it in place with using gravity or another limb, or apparatus. It might feel nice, but what are the physiologic changes that happen as a result? What are we influencing? Well, under most circumstances we’re likely to be distending both the contractile tissue (musculature) and non-contractile tissue (eg tendon, fascia), and indeed the interface between i.e. the musculotendinous unit (MTU).

The effects of a single stretching exercise on performance are highly dependent on the stretch duration and stretching technique, or type. That is to say, the observed changes to performance parameters resulting from a 60s static and passive stretch will likely be different to a 30s stretch of the same type, and this is where a lot of the confusion arises.

Okay, so lets’ first look at the potential negative effects of static stretching on performance, as cited in the literature.

- Increased electromechanical delay (EMD) [muscle switch-on times, read more about EMD here]

- Decreased muscle strength

- Decreased muscle power

Is this really true, and why might this happen. Indeed many authors have reported impaired performance in muscle strength and muscle power-based activities following stretching (see e.g. Magnusson 2006 below). Impairments of up to 30% immediately post stretching have even been reported (Fowles et al. 2000).

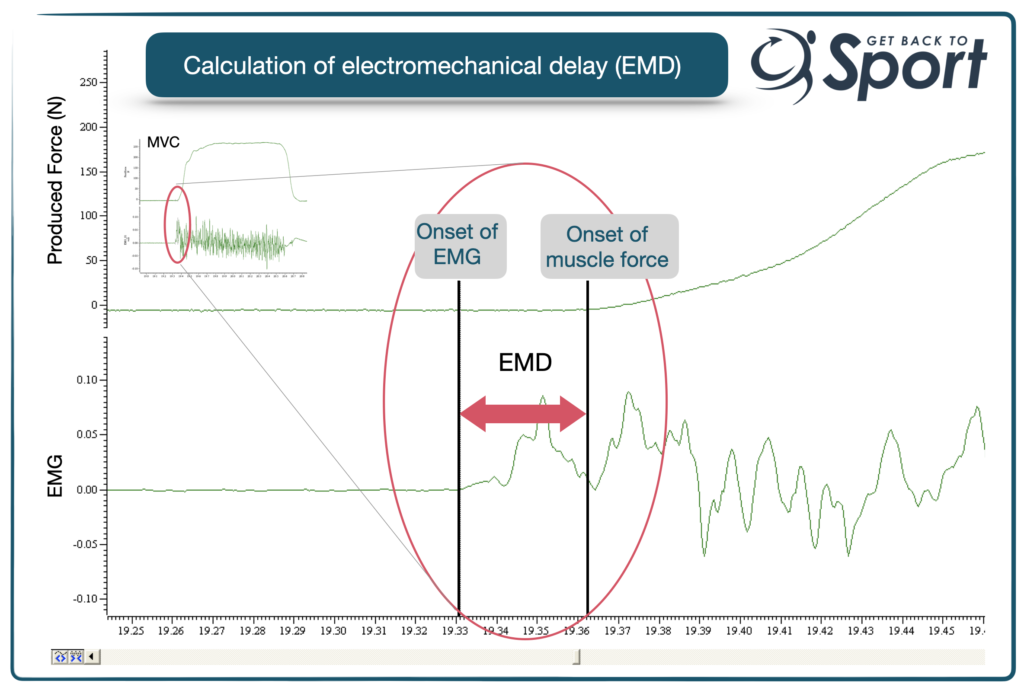

EMD, which is typically defined as the time delay between the start of muscle electrical activity (EMG) and initiation of muscle force production (see figure below) is an important tempero-force characteristic of muscle performance. Likewise, acute episodes of stretching have shown an increase in this delay (e.g. Costa et al 2010).

This means, the longer the EMD, the longer it takes to initiate force, which isn’t great for power-based performance, or indeed for injury avoidance.

What are some of the reasons to explain these negative changes? Well, static stretching has been shown to increase compliance of the MTU and, or, decrease muscle stiffness (Konrad et al. 2019)- which is what we want to increase ROM, right? It’s also been shown to negatively affect motor unit recruitment, and a few other things as well. Given that good strength, power and EMD performances require fast twitch motor unit recruitment, synchrony of motor unit firing, and power and EMD are also heavily influenced by compliance (stiffer systems transmit force better), you can see how these performances might be impaired following stretching.

Keep Stretches to Less Than 60 Seconds

Don’t panic! When we delve into the literature a few things become apparent to make us reconsider ditching all our well-meaning pre-exerise interventions.

Firstly, most of these negative changes to performance have been observed following stretches of 60 seconds or greater. When we reduce the duration of stretch to less than 60 seconds, the effects on performance seem to be trivial.

Furthermore, these studies often investigate stretching in isolation, when in reality stretching is most likely performed as a part of a warm-up routine involving some dynamic activity. When researchers seek to evaluate performance changes to static stretching when performed at a part of a warm-up, again these dramatic changes to performance are diminished. It might be that some of the positive physiological effects of warm-up-associated increases in muscle temperature, like increased muscle fibre conduction velocity, binding of contractile proteins could offset any deleterious effects.

What About Other Forms of Stretching?

When we look at the literature, particularly the systematic reviews and meta-analyses (See Behm et al 2016; Chaabene et al. 2019) it appears as though the more dynamic-type stretches also have a trivial effect on performance, especially when short duration (<60s) and conducted as a part of a warm up. Dynamic stretches may actually be beneficial to performance (~1% improvement).

Does Stretching Impair Strength and Power?

I think you can make this conclusion now. Acute static stretching may have a have a negative effect on strength and power if the duration of stretch is >60s. Depending on the volume of stretching performed (i.e. how many episodes of 60s+ in a session), this impairment could range from 3%-30% (the latter resulting from 30 min of time under stretch). Under most circumstances, stretching of short duration and as a part of a warm-up will not negatively impair performance.

However, in elite settings or perhaps in rehabilitation where the subsequent exercise requires good strength or power performance and adaptation, perhaps place the longer duration stretches in another session.

References

- Magnusson & Renström. (2006). The European college of sports sciences position statement: the role of stretching exercises in sports. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 6, 87–91. (ResearchGate)

- Fowles, et al. (2000). Reduced strength after passive stretch of the human plantarflexors. J. Appl. Physiol. 89, 1179–1188. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1179

- Costa et al (2010). Acute efects of passive stretching on the electromechanical delay and evoked twitch properties. Eur J Appl Physiol. 108:301–310

- Konrad et al. (2017). The time course of muscle-tendon properties and function responses of a five-minute static stretching exercise. Eur J Sports Sci (ResearchGate)