Welcome to post 63 of Strength and Conditioning for Therapists!. I’ve loved writing this post: do we need to resistance train to fatigue? It’s a provocative topic and I hope that you enjoy the read. Please feel free to tweet, tag me, comment, add to the debate; I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Training to fatigue (or failure) or not?

So you may have been made aware of a paper that came out last year by Viera et al (2021, ref below) that investigated the effects of resistance training to failure compared to training not to failure on muscle strength and hypertrophy. The concluding remarks in the abstract were that “Resistance training not to failure may induce comparable or even greater improvements in maximal dynamic strength and power output” [compared to training to failure.]

This systematic review (SR) and meta analysis (MA) made it on to the best papers of the year list of a few, including Adam Meakins, who also put a few ‘thoughtful’ faces after this quote in his highlight on Twitter. Rightly so in my opinion.

So, what I’d like to do here is review this MA and provide an explanation as to:

- Why you shouldn’t take this blanket conclusion as read and mistakenly assume similar benefits in your resistance training and rehab interventions across patient groups.

- Why some of the research included in this SR and MA shouldn’t have been included – and thus may skew the results, and your interpretation.

Do we need to resistance train to fatigue?

Right. If you stop at the abstract, avoid reading the full paper and attempting a critique, one could mistakenly conclude that a programme of 5 reps of resistance exercise not to failure (with perhaps even another 8 reps in the tank) would give similar strength & hypertrophy gains across all populations compared to a programme of 5 reps of resistance exercise to failure.

The above assumption is incorrect. Whilst something is almost (!) always better than nothing, we still need to consider the basics of exercise prescription, which include intensity of exercise, rest and of course the baseline characteristics of the patient/individual.

Is the exercise challenging?

Consider the fundamentals of exercise prescription

Train to fatigue or not to fatigue?

Question:

Would you assume a similar strength gain in young healthy males of a 3 x 8 rep protocol performed 2 times per week, one performed to failure (I prefer failure not fatigue, see why here) and one performed at an intensity of 10% 1RM. Probably not I’m guessing.

Here’s a reason why:

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Schoenfeld et al. (2017 – ref below) illustrates this nicely. Analysis of data comparing low- and high-load resistance training protocols show that maximal strength benefits are obtained from the use of heavy loads vs lighter loads.

This is likely due to motor unit recruitment. Low resistance not to failure protocols are unlikely to recruit optimally from the fast, high-threshold motor units – you know, the ones that produce most force?!

Fatigue and rest

Question:

If you design a high-intensity 5RM strength training protocol, would you assume optimal strength gains would be made if only 30s of rest was provided between sets, versus 2 minutes for example. Again probably not. What is your reasoning?

Here’s one reason why:

Yes there’s debate on the issue of rest, however, in my opinion, this debate is largely dictated by the components of the resistance training (intensity) and the baseline status and characteristics of the individual. We’re trying to recruit from that high-threshold motor unit pool, repeatedly. Remember that high-threshold, fast twitch fibres are fatiguable. If you provide insufficient rest between sets then the ability to recruit in the next set is compromised, as is your max strength training stimulus.

Who is your patient / client?

Question:

Would you provide the same resistance [strength] training intervention to novice exercisers and accomplished resistance-trained individuals? Again, probably not.

Here’s a reason why:

As I’ve reported before (here), individuals habituated to resistance training likely require a larger stimulus for adaptation compared to novice resistance trainers. In this article I summarised the research from a variety of quality sources and provided a synopsis (including ** below). Ultimately, whilst the the reasoning is likely varied explaining the differential stimuli likely required, it is important to consider the individual in front of you to avoid ineffective or overly challenging resistance training and rehab interventions.

So, train to failure or not to failure?

Back to the Paper by Vieira et al. and another reason why to not take a blanket approach to training.

In order to meaningfully answer the question of training (or rehabilitating) to failure vs. not to failure we need make fair comparisons across high quality studies. Vieira et al. did attempt to do this by offering a subsection of results based on equivalent training volumes between studies. That is to say, where individual RCTs have ensured the same, or similar number of repetitions performed in groups that train to failure and those that don’t.

Equating volume is not enough

Whilst this is useful, volume alone is not sufficient to generate fair comparisons. To exemplify, let’s take the study by Folland et al. (2002), which is ref 13 in the Vieira paper. Disclosure here, Jonathan Folland is a former co-author of mine, but this in no way influences this synopsis or interpretation.

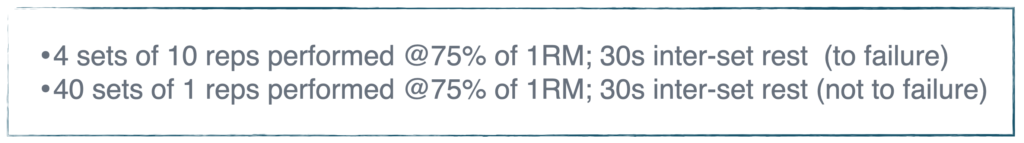

Folland et al. randomly allocated 23 healthy recreationally active young males and females into 2 resistance training groups:

Take a look at the design of these protocols. What do you notice?

You will see that:

- Exercise intensity is matched

- Volume of exercise is matched

- Rest is matched

So, what’s the problem? Are you happy with the inter-set rest interval? Think about what we discussed above.

Whilst we might want to achieve some degree of fatigue within a lower intensity, higher rep set to elicit fast twitch motor unit recruitment (which happens towards the end of this type of set), between sets we would still want full motor unit recovery so that we can repeat the set with the same intensity.

Likewise, and probably even more important for higher-intensity lower rep sets where fast twitch motor unit recruitment is achieved (ideally) from the start, sufficient rest between sets will enable this to happen.

Now, this is most definitely not a criticism of the Folland study. I’m questioning the appropriateness of including this paper in the SR and MA by Vieira et al as the strength stimulus in the Folland paper is not optimised. In fact when we look at the paper by Folland et al, it’s clearly stated that the aim of their study was to investigate the role of the metabolic stimulus in muscular adaptation; as such their protocols were designed to elicit this (or not).

Looking at the above study and taking into account the insufficient rest in the 4 x 10 protocol, I (and maybe you) would guess that greater maximal strength gains would be achieved in the 40 x 1 protocol vs the 4 x 10. Why? The amount of inter-set rest and recovery. Indeed this was the case! The metabolic consequences (fatigue) actually got in the way of optimising strength adaptation.

In my opinion, this is problematic for the Vieira et al MA as it inappropriately adds weight to the MA that training not to failure is superior than training to failure. There’s no room for consideration of intensity or inter-set rest.

Summary

At the risk of producing an entire manuscript myself here, I’ll pause my review here.

What I’m trying to get across is that:

- Read more than the abstract

- Consider all the variables

- Does what you’re reading seem reasonable and practicable

- Use your common sense and

- PLEASE consider the fundamentals of exercise prescription

Please tweet this, comment, add to the debate, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

References

- Viera et al (2021). Effects of Resistance Training Performed to Failure or Not to Failure on Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Power Output: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. J Strength Cond Res 35(4): 1165–1175 [Abstract]

- Schoenfeld et al (2017). Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- versus high-load resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis J Strength Cond Res 31(12): 3508–3523 [Abstract]

- Ralston et al. (2017). The Effect of Weekly Set Volume on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med.47: 2585–2601** [Full text]

- Kubo et al (2020). J Strength Cond Res J Strength Cond Res 35(4):879-885** [Abstract]