Hello and welcome to post 65 of the Strength & Conditioning for Therapists series. Last time we explored the fundamentals of periodisation within training programmes. In this post we’ll delve into using periodisation in rehabilitation. Specifically, why we should not only consider it but how we can simply, and must, achieve its integration.

Periodisation as a Tool in Rehabilitation

Why should we view using periodisation in rehabilitation as a standard approach? Arguably it’s a strength and conditioning term and process and as such its utility lies within optimising sporting and athletic performance. True, possibly in many rehabilitation settings performance optimisation isn’t a key focus, well in the earlier stages of rehabilitation anyway. But as we highlighted in the previous post, patients, even if you’re not dealing with patients with performance aspirations, they will still likely need to make quite substantive improvements and across in across a range of indices. Having a process that would support optimisation of yours and your patient’s efforts would surely be of benefit, right?

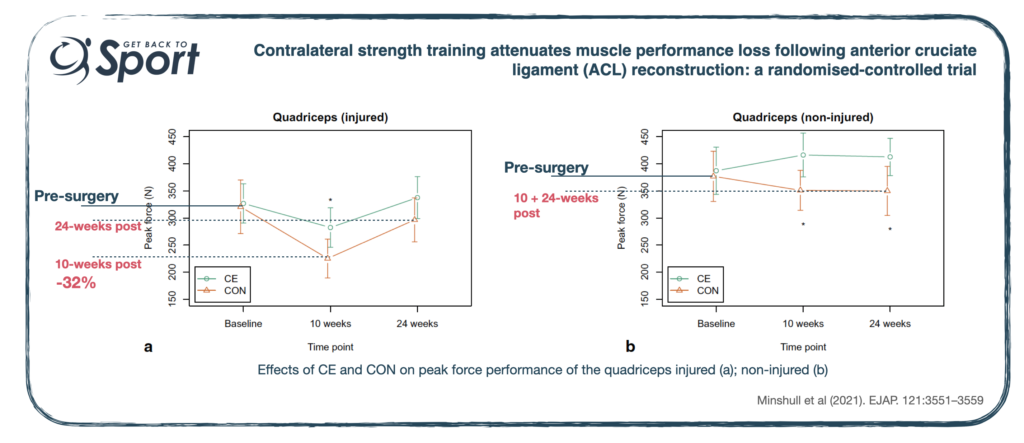

Take ACL rehabilitation post reconstructive surgery for example. At 10-weeks post surgery we’d likely expect around a 30% loss of knee extensor strength compared to pre-surgery (Minshull et al 2021), so at the very least we need to recoup this (and I would suggest more!) during rehabilitation.

We also know that other indices of performance like rate of force development (RFD) and sensorimotor performance (proprioception) are also impaired, by simlar levels. Given the mounting evidence that suggests that some deficits still remain 2+ years post surgery (Tayfur et al 2021) and that training intensely for multiple outcomes can impair adaptation, it’s perhaps more of a necessity than a consideration to use a periodised framework if we want to be most effective.

The Utility of Periodisation

As we’ve already covered, there are several approaches to periodisation: linear, non-linear, blocked … I think the first real utility of periodisation within rehabilitation settings is in facilitating the management a multitude of different rehabilitation outcomes.

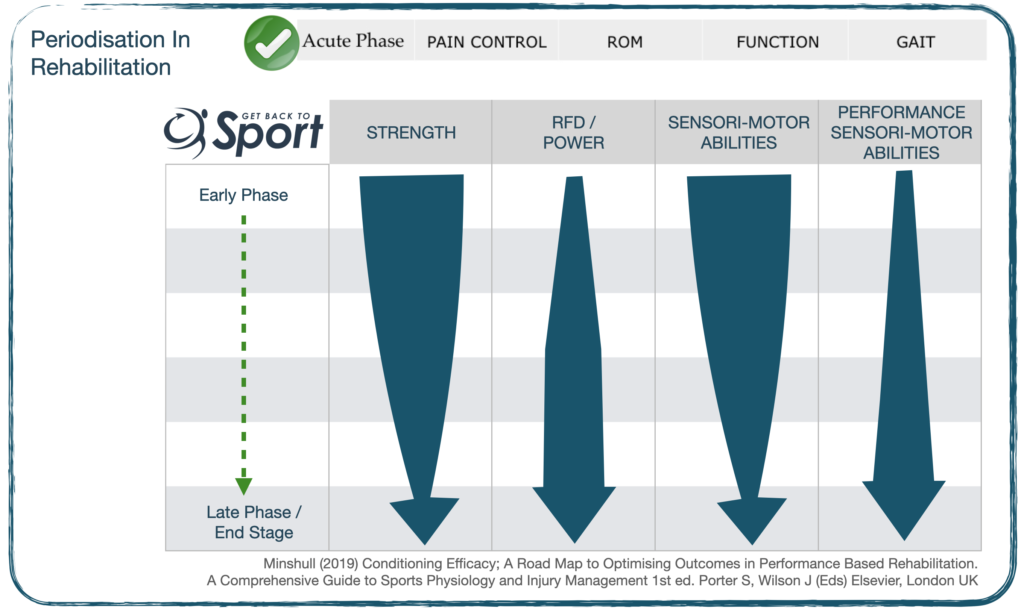

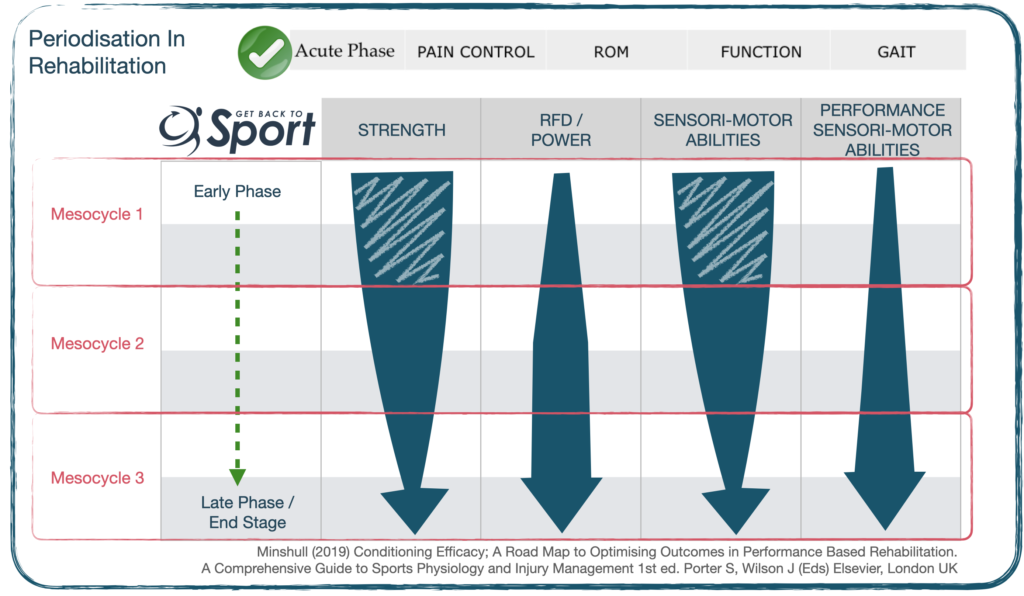

The Hierarchy of Importance

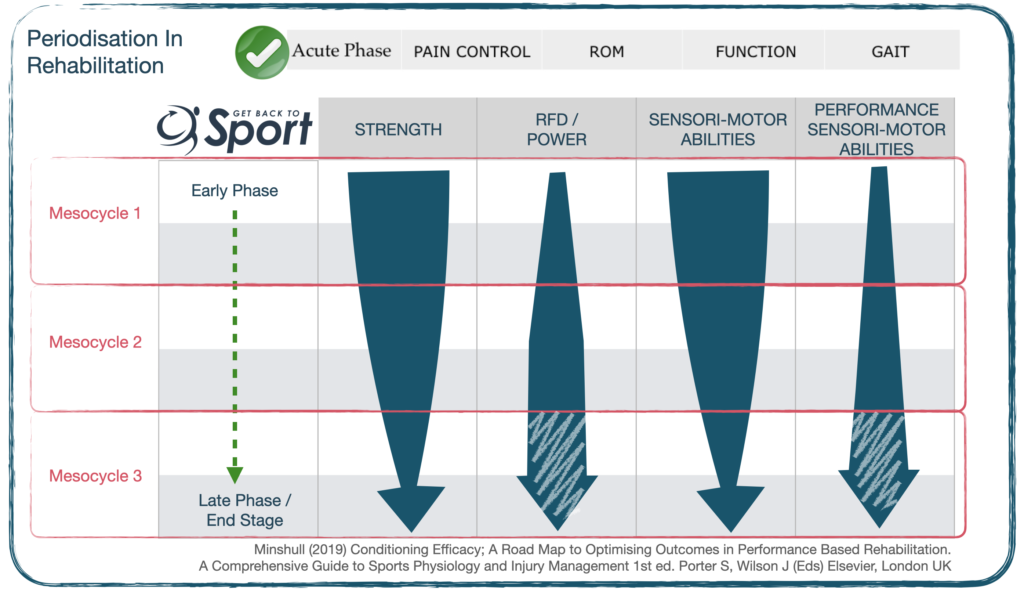

What do we mean here? Well, it’s establishing what’s most important at which points in the rehabilitation cycle. A hypothetical example of establishing a hierarchy of importance of some of the neuromuscular factors within an ACL rehabilitation programme is shown below. After addressing the ROM, pain and restoration of gait in the acute post-operative phase, we know that we need to work on things like muscle strength, power, proprioception. We also know that we can’t do all of this at once and there needs to be a plan that will progressively take the patient from this early phase through to end stage and return to play, if required. If we put all of these things in a plan, or macrocycle it might look a bit like this.

For me in this setting, and indeed in most rehabilitation settings the principal focus in the early stages of rehabilitation has got to be muscle strength development (see why here) and sensorimotor (proprioception) abilities. This would be the first mesocycle. See the size of the arrow in each mesocycle changes indicating a change in focus of rehabilitation.

As strength and control is improved and the focus of rehabilitation shifts towards expressing this force capacity – i.e. improving explosive muscle force production (RFD); finally culminating in the performance-sensorimotor abilities, whereby dynamic exercises are representative of the sports-specific demands and threats.

By the time we reach the final stages of a rehabilitation programme and prepare for return to play, the athlete should have achieved the required foundations in strength, explosive force production and ‘static’ sensorimotor performance. The focus becomes being able to deploy it functionally by exposing them safely to unpredictable, less stable scenarios; in effect practising for the ’emergency scenario’. For example building from low velocity directional change drills within the sports-specific environment (i.e. on the pitch, court) to high velocity directional change drills involving performance tasks, subtle changes in surface stability and perturbations.

Periodisation in Non-Athletes

So you can see that I’ve used a sporting example of using periodisation in rehabilitation. Please don’t think that the utility of periodisation lies only in the rehabilitation of athletes. It can absolutely be applied to non-athletes alike. Think about the non-athlete patient populations that you see, think of all the different elements of function that need to be restored. In some settings it might be quite simple and you only have a couple of things to focus on.

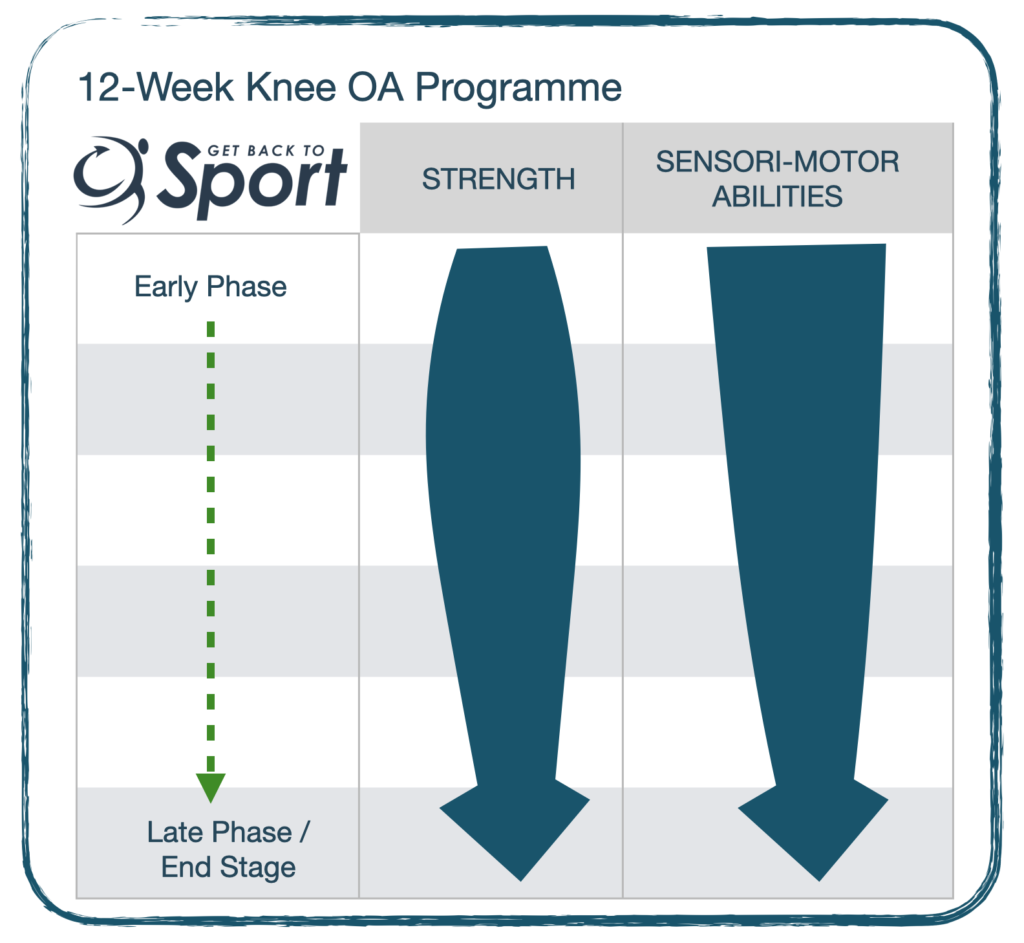

For example, in a 12-week OA programme I never really get out of the strength phase, particularly in those individuals who are new to resistance training. So we have a very fat arrow all the way through! We need a progressive approach to building people up, both physically and psychologically to be able to lift heavy loads. Also they are typically very weak, as such we really do need a good 12-weeks to have a chance of developing a decent strength adaptation. Sensorimotor performance, or proprioception is also very important and training this alongside strength isn’t counterproductive. Just consider when you do these exercises relative to a challenging strength session.

But where we are perhaps managing restoration of ROM, strength, proprioception, power, etc… using a periodisation framework can help to align your thoughts. Develop a hierarchy of importance – what to focus on and when; what’s most urgent? How then to progress from one thing to the next. You can change the headings of the table and the size of arrows.

Summary

So there we have it. I hope that this has been helpful and perhaps thought provoking? Also that this framework provides you with a time-saving strategy. Yes it might take little time to map out the rehabilitation plan at the start, but in doing so you’ll maximise the opportunities to be most effective and minimise the opportunities for redundancy of effort – and overall save time!

COMING VERY SOON!

Look out for these – Masterclasses from some of the best names in the areas of S&C, Exercise Science, Research, Academia, Practice … on pertinent topics in S&C as applied to rehabilitation

References

- Minshull, C et al (2021). Contralateral strength training attenuates muscle performance loss following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: a randomised-controlled trial. Eur J App Physiol 121(7)[Link]

- Tayfur et al (2021). Neuromuscular Function of the Knee Joint Following Knee Injuries: Does It Ever Get Back to Normal? A Systematic Review with Meta‐Analyses. Sp Med 51:321–338 [Link].

- Minshull, C (2019). Conditioning Efficacy; A Road Map to Optimising Outcomes in Performance Based Rehabilitation. IN: A Comprehensive Guide to Sports Physiology and Injury Management 1st ed. Porter S, Wilson J (Eds) Elsevier, London UK.