Hi everyone and welcome the third in this three part series on the effects of lockdown on physical and psychological health and number 53 of Strength & Conditioning For Therapists. Last week Serena Simmons talked about the psychological impact of lockdown, the propensity to disengage from exercise and some strategies on how to support behaviour change. Today we’re going to look at the physical reconditioning part; minimising losses, maximising gains in lockdown.

Lockdown: Expected Losses To Physical Performance

A couple of weeks ago in the first of this series [here], we looked at the potential impact on strength and fitness caused by decreased physical activity. Such included between 10-25% losses in muscle strength, muscle size and cardiovascular fitness over a 3-month period, with the most extreme changes being associated with the greatest restriction to physical activity.

With the COVID-19 virus appearing to stick around for some time to come and partial lockdown restrictions being applied in a multitude of locations, what can we do to minimise the impact?

Minimising Deconditioning

As I mentioned last time, much of the research into what happens to physical performance and the properties of musculoskeletal tissue is derived from bed rest, immobilisation and or detraining studies. The bed rest model is usually used often with 2 applications –

- 1. An approximation of what might happen during hospitalisation

- 2. (Head-down bed rest) An approximation of what might happen during space flight

In the current context – what’s happened since COVID lockdown, it represents an extreme example of change, but it also permits the testing of measures that mitigate the associated losses to physical health. There’s a wealth of literature on this, but I’ll just flag up two potential strategies, which might be relevant if we go back into -partial – lockdown.

Minimising Losses: Nutrition to Minimise Deconditioning

There’s a huuuuge body of research that focusses on nutrition and its potential role in attenuating declines and maximising physical health – or minimising losses & maximising gains. In this context a significant proportion of this research is devoted to protein / amino acid supplementation during bed rest.

Let’s look at the reviews here, save a rather large post. So, about 9 years ago Stein & Blanc (2011) reviewed whether or not protein supplementation prevents muscle disuse atrophy and loss of strength. Only six published studies were identified that investigated amino acid supplementation , three showed benefit, three did not. On a careful scrutiny of the data they suspected an insufficient supplementation level of protein, based on out-dated RDA recommendations.

Conclusions? The results were equivocal, that is to say it wasn’t possible to conclude whether or not protein supplementation protected against the losses to muscle strength and size.

More recently, this year in fact, Sandal et al. (2020) conducted a a systematic review on an array of different nutritional measures to ameliorate musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary deconditioning in space flight analogues (i.e. bed rest). They also concluded that there was a limited amount of high quality studies investigating the effect of nutrition as a standalone countermeasure on outcomes. And that the findings do not support that nutrition alone will be effective in maintaining musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary integrity during space flight and bed rest.

Clearly, there’s a lot more research no this topic, but on balance it seems, that we need to do more than just get the diet ‘right’ during bed rest and inactivity to minimise losses.

Minimising Losses: Exercise & Nutrition

How about exercise as a strategy to attenuate declines – seems reasonable right?

Lee et al. (1985). Ran a small-ish study to evaluate the effects of nutrition OR exercise to prevent muscle deconditioning during bed rest in women. 24 women were assigned to an exercise (n=8), a no-exercise control (n = 8), or a no-exercise protein supplementation group (n = 8). The exercise was performed supine, on a treadmill, and performing maximal concentric and eccentric leg- and calf-press exercises. Protein supplementation was 1.6 g·kg(-1)·day(-1) (vs. 1.0 g·kg(-1)·day(-1) in the control group). The results showed that the exercise protocol of resistive and aerobic exercise training protected against losses in strength, endurance, and leg lean mass. AND a nutritional countermeasure without exercise was not effective (again).

Interestingly, in women who were more fit at baseline, the exercise countermeasure was less effective and losses to strength, endurance and lean leg mass were greater compared to the other groups. Remember here that this is a very small sample, but also it also suggests that the more you have, the more you have to lose..?

Another study with a (strangely) very similar design and sample (Trappe et al. (2007)) showed the same: a nutrition countermeasure was not effective in offsetting lower limb muscle volume or strength loss during 60 days bed rest. The concurrent aerobic and resistance exercise protocol was effective at preventing thigh muscle volume loss, and thigh and calf muscle strength loss, but by about 75%.

So, it seems as though exercise of some description is far more effective to attenuate declines associated with disuse than any stand alone nutritional intervention.

How Much Exercise?

The answer to this question really depends on many things, including the characteristics of the person. Here’s a good example, however, of how doing something, even if just a little, can mitigate the losses associated with detraining.

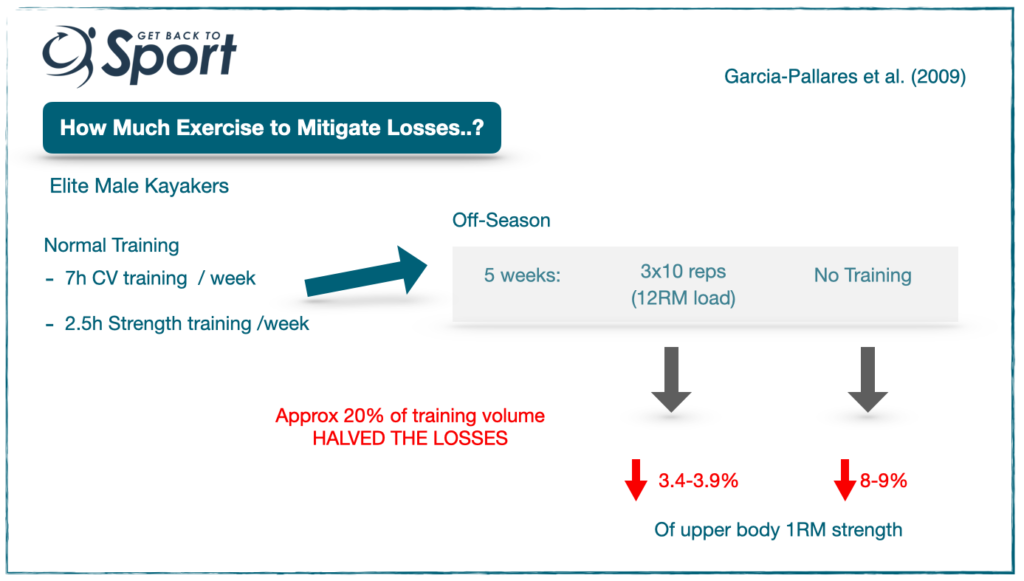

Garcia-Pallares et al. (2009) [I’ve mentioned this study before] conducted a nice study to evaluate reduced training volume of the CV fitness and strength of elite kayakers. Their typical training volume comprised of 7 hours CV work per week and 2.5h of strength work per week, representing 10-15 and 3 sessions, respectively. They then reduced this to 5 weeks of only 1 session of strength (bench press, prone bench pull and squat exercises) and 2 endurance sessions (1 kayak, 1 run) each of 40 mins.

The data showed that by the end of the 5-weeks, losses to muscle strength were halved by comparison to the no exercise group. And the effect was similar for CV fitness parameters. Yes this is an elite group, but we know even moderate physical activity has a positive effect on preserving muscle mass and power in older adults and this is perhaps a nice model to follow.

You may notice that the loading – 12RM isn’t optimal for strength gain…but it did have an effect on mitigating losses. Again, I’ve discussed this in depth in a prior article, but if you’re limited with respect to facilities and resources to generate optimal overload, the key takeaway here is:

If you can continue training at a high intensity, as little as 20% of your normal workout volume may be sufficient to cut your performance losses in half (compared to if you stopped training all together)

Maximising Gains; Retraining After Lockdown

The exemplar study design to examine these effects are the training-detraining-retraining studies. I wrote about this a few months ago when we were in full lockdown here in the UK and many other countries – how to avoid detraining in lockdown. Here’s another study to add into the mix.

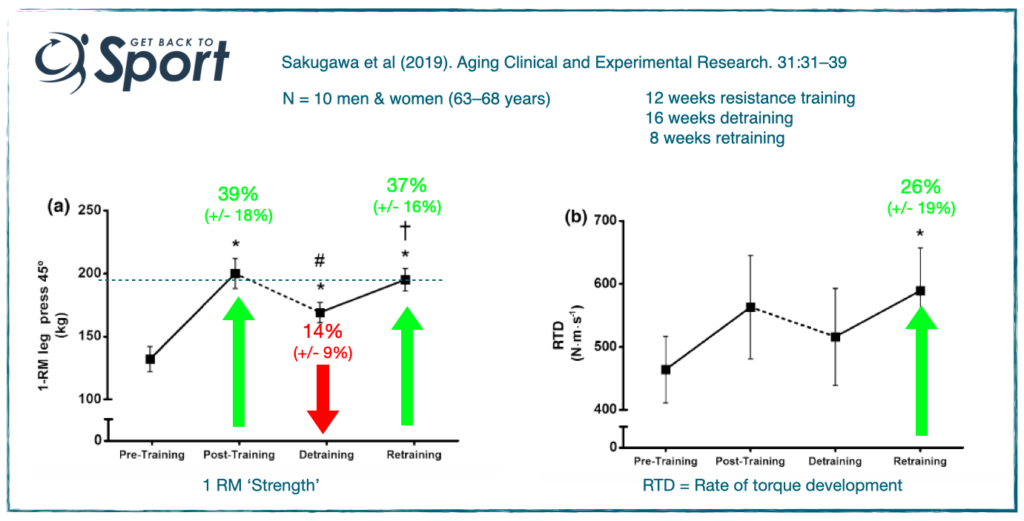

Sakugawa et al (2019). Examined the effects of 12 weeks of training, 16 weeks of detraining, followed by 8 weeks of retraining on several muscle and functional parameters. I’ve illustrated the strength and rate of torque development data below.

Strength, as assessed by 1RM leg press, increased by almost 40% over the 12 weeks. After the 16-week detraining period strength decreased by only 14%, and to restore levels to that achieved by the training took only a further 8 weeks of training. A similar pattern was observed for some of the functional parameters. RTD (RFD) data looked to follow a similar pattern, however this index is notoriously more variable and you can see that the changes observed were only statistically significant for the last data point.

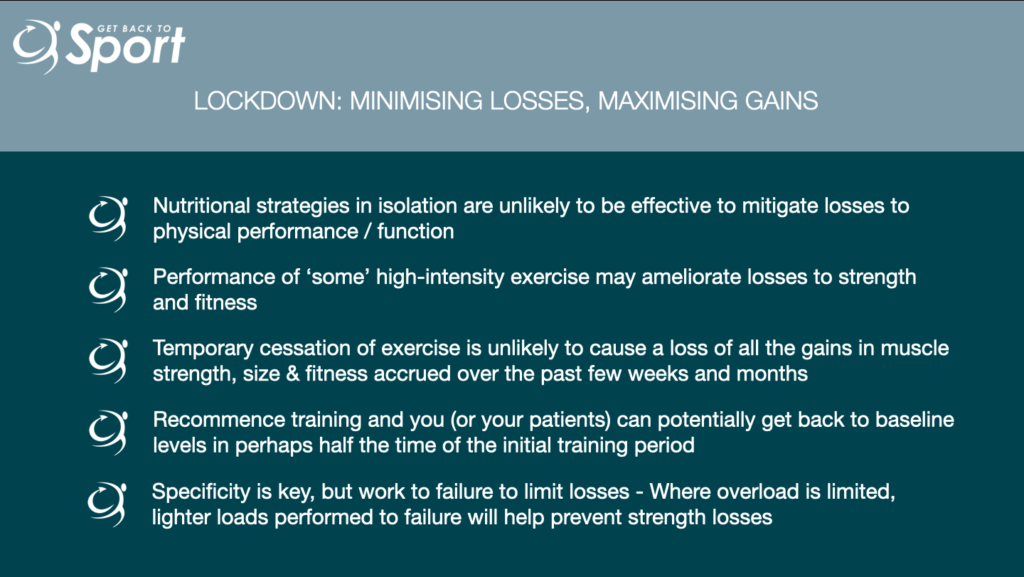

When we summarise the message from the above studies and those that I spoke about in the previous post :

- You (or your patients) are unlikely to lose all the gains in muscle strength and size accrued over the past few weeks and months if you cease training for the equivalent period, or perhaps longer

- Recommence training and you (or your patients) can potentially get back to baseline levels in perhaps half the time of the initial training programme.

Summary

Right, so what can we take from all of this information? Minimising losses and maximising gains in lockdown.

Liked this? Want some more? I have some exciting news. The Masterclass series is now available.

References

- Stein & Blanc (2011). Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 51(9):828-34

- Sandal et al (2020). PLoS One. 9;15(6):e0234412

- Lee et al (1985). J Appl Physiol (1985). 15;116(6):654-67

- Trappe et al (2007). Acta Physiol (Oxf) 191(2):147-59

- Sakugawa et al (2019). Aging Clin Exp Res. 31(1):31-39