Hello Everyone! It’s been a few weeks since I posted on the S&C for Therapists blog. I’m delighted to recommence with a 3-part series on the effects of lockdown on physical and psychological health, and what some of the key interventions might be to deal with these. Today we’re focussing on COVID-19: Effect of lockdown on physical health; post 51 of Strength & Conditioning For Therapists. In the next post Psychologist Serena Simmons talks about the effect on mental health.

Before we get into this, I realise that there are many who’ve used the period of lockdown to take up a new form of exercise, or found the motivation to do more physical activity (PA). This is fantastic, and your interaction with these people in clinic is likely to be as result of increased and, or novel, training load causing overuse injuries and acute MSK issues.

But there’s another sub-population who, have disengaged from PA, exercise and training and are now suffering the effects of sedentary behaviour on their physical (and mental) health. For younger populations, this might be the start of a trajectory of sub-optimal health behaviours and its consequences. For older populations the consequences are potentially greater and this might represent the start of a dramatic spiral of decline in physical function.

Does a lack of physical activity matter?

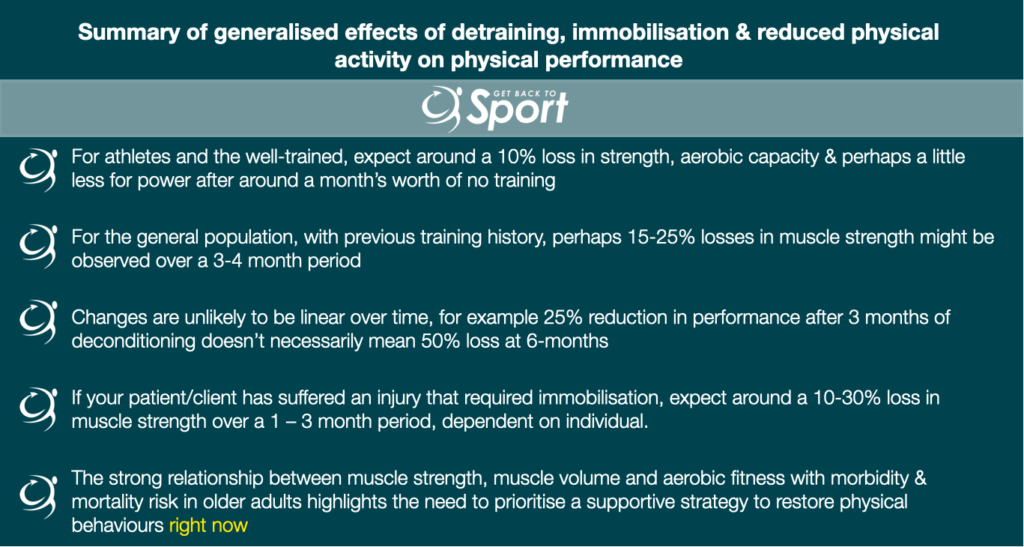

Losses to physical performance capabilities associated with sedentarism, such as strength and aerobic capacity (VO2 max) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. These changes are often compounded by sarcopenia in older populations, such that the risk of these consequences occurring are greater (Narici et al. 2020). Need I say any more? I’m sure you can predict the cascade of consequences this will have for the individual and wider society.

In fact, last year I reported on a paper that estimated the cost of sarcopenia (the age-related loss of muscle size, quality and strength) to be £2.5 billion per year in the UK alone.

On the positive side, maintaining high physical activity levels preserves muscle mass and power throughout the lifespan (Grassi et al.1991). This benefit translates into a gain of 20–25 years of biological age when comparing master athletes, weightlifters and sedentary individuals (Narici et al 2020). So, if we can reinstate habitual PA behaviours we may have a chance of restoring this protective effect.

Why did lockdown stop people exercising?

There’s a complex milieu of factors that will have contributed to this disengagement in PA and structured exercise that we need to address, many of which are psychological. Our esteemed resident Psychologist, Serena Simmons, will be covering this in the next blog. The purpose of this article is to understand the potential effects of lockdown on physical health and performance that you might expect to see in your clinic caused by this period of disengagement in PA. And I say potential, because we really don’t know the full extent of this problem yet.

Subsequent articles will focus on how to reinstate behaviours, training and restore (and improve) physical and psychological capabilities.

What are the effects of sedentarism on physical performance?

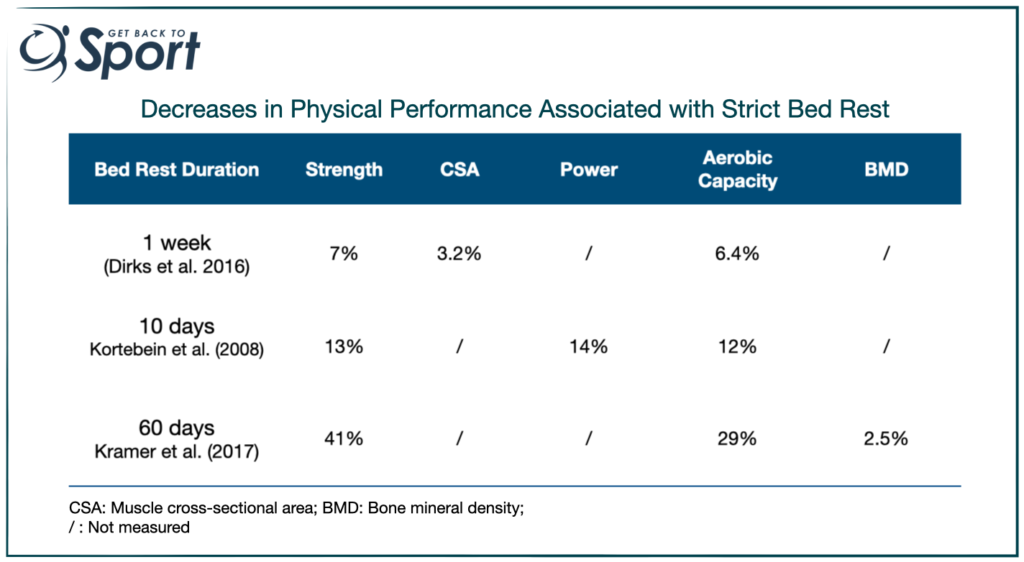

As I’ve discussed previously, much of our estimations of what might happen to physical performance subsequent to a period of inactivity are derived from bed rest and immobilisation studies. Below are the results of a few bed rest studies that range in duration. There’s also the 21-day bed rest study by Krolner et al. (1983) to add into the mix, who reported a 09.% reduction in BMD per week.

The same dramatic changes are also visible if you immobilise a limb, but permit the individual to otherwise go about their daily activities. Wall et al. (2014) casted one lower limb of healthy male participants for 5 or 14 days and recorded d a 9% reduction in quadriceps strength after just 5 days and a 23% loss after 14 days. These changes were accompanied by 3.5% and 8.4% reductions in muscle CSA at 5 and 14 days, respectively. Others have found similar, changes at around 3-months. For example up to 30% loss in leg strength after 90 days of immobilisation (Alkner & Tesch, 2004).

Granted, it’s unlikely that the majority of the population who’ve disengaged from physical activity are immobilised, but this does give us an estimate of a worst case scenario.

A more reasonable approximation would be the results of studies that have investigated inactivity and, or, detraining. So, what do these tell us? Well again, there are a few ways in which we can look at this. For example there are the intervention studies, whereby the effects of cessation of structured training in a trained population are examined. Then there are the larger population studies, often cross-sectional, that look at the physical health and performance attributes of individuals who are sedentary. Let’s have a look at some of these.

Effects of lockdown on physical health

Athletes & performance

Garcia-Pallares et al. (2009) conducted a study looking at different post season recovery strategies on the CV fitness and strength of elite kayakers. In the 5-week off-season one group performed no structured physical training for 5 weeks and one group performed just one maintenance session per week (I talked about the benefits of this earlier in lockdown). This is compared to a typical training volume of 7 hours CV work and 2.5h of strength work per week.

By looking at the control group, we can make some estimation about the effects of lockdown on physical health and performance losses in highly-trained individuals. At the end of the 5 week period, the control group who did no training lost 8-9% of upper body 1RM strength (bench press and bench pull), lost 10% in VO2 max and 3.2% in paddling power. So, not quite as dramatic as immobilisation, but nevertheless substantial changes in just over a month.

Training-detraining studies

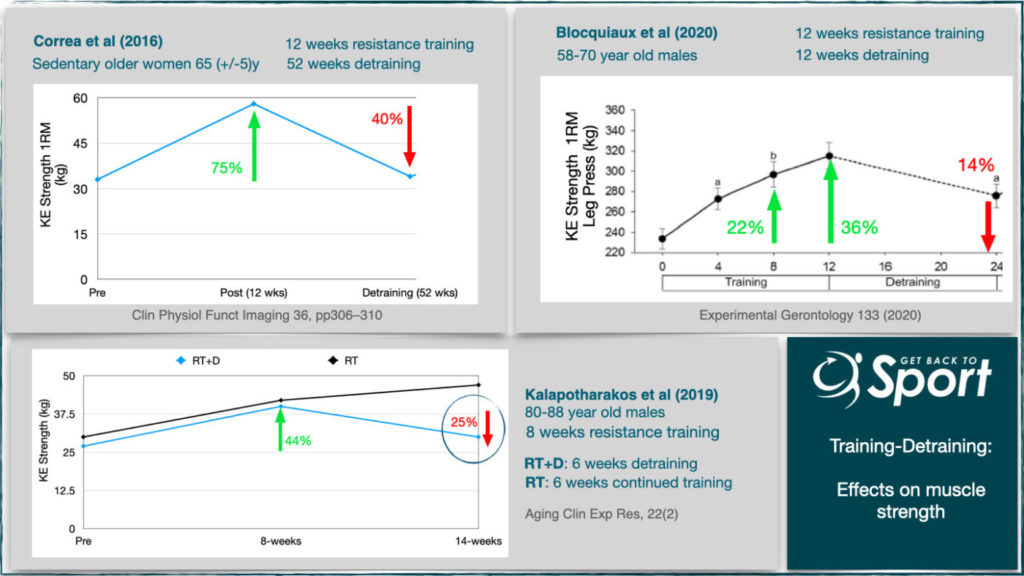

Another way to look at the extent and rate of deconditioning is to take a population, give them a standardised dose of training and then remove it. Again, I covered this topic in a bit more detail in one of April’s posts. What we can see is that not all the training gains are lost for an equivalent period of deconditioning. For example, let’s say a 58-70 year old male commenced strength training in December 2019, given the right dose, he could expect to make a 30-40% improvement in strength. Then lockdown happens, he stops training for 3 months in March, on his return to the gym in June (lucky him), he may have only lost half of the strength gain that he previously made (see Blocquiaux et al 2020 in the picture below).

This retention of prior strength may remain for several weeks (see above), but after a year or so, maybe not.

Now I’m generalising and extrapolating a fair bit here. In reality the effects of on different individuals and populations over different timeframes is likely to yield different results to the data presented here. BUT, nevertheless this may give us a framework to make estimations.

Sedentary vs. physically active: Non-athletes & older populations

Narici et al (2020) published a great paper very recently that covers much of what we’re talking about here (and more!). In it they refer to a study by Kyle et al. (2004), who conducted a survey on 6733 people aged 18–98 on the impact of sedentarism. Maybe not a shock conclusion, but the study clearly showed that PA was successful in maintaining fat-free mass, prevented excess body fat and resulted in lower rates of obesity. And when we look throughout the lifespan, studies clearly show that that maintaining a high PA level preserves muscle mass and power (Grassi et al. 1991).

These findings taken together with the known effects of ageing on muscle, really highlights the threat of a pandemic of sarcopenia and a tremendous increase in the consequences. These include compromised quality of life, independent living and increased mortality rates

Read more here

Whilst it is definitely important for the general population to recommence activity for a multitude of health reasons, in my view it is especially important right now for us to focus on those older populations, who are perhaps more fearful and hesitant at returning to exercise. We need to provide a safe environment and framework to help them recommence PA and structured resistance exercise, as a matter of urgency.

Can we restore physical health & performance after lockdown?

The good news is that even following prolonged periods of largely sedentary behaviour, it is still possible to improve physical health and performance. So, the effects of lockdown on physical health can be improved, and maybe even reversed. And for acute periods, this might not take as long as it did to generate the training effect. This, will be the topic of the final blog in this series, so stay tuned.

There’s so much more we could talk about here, including metabolic health, mechanisms etc. but this post would go on forever. So let’s sum up; what can we glean from the literature on the potential physical changes in our clients and patients?

Summary

Would you like to lean more about Strength & Conditioning and how to apply this to patients?

Strength & Conditioning For Therapists

The formula to optimise patient outcomes

Achieve continued improvements in patients’ strength outcomes. Adapt and modify traditional resistance training exercises without losing the specificity and strength gaining stimulus within 40 days.

Check out the my hugely popular Strength & Conditioning For Therapists online course. There are just 2 enrolments per year, so make sure you’re on the list to get all the info.

.

References

- Grassi et al. (1991). Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 62(6):394-9

- Dirks et al (2016). Diabetes 2016 Oct; 65(10): 2862-2875

- Kortebein et al. (2008) The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 63(10),1076–1081

- Krolner et al. (1983) Clin Sci. 64: 537-540.

- Kraemer et al (2017) PLos One. 12(1)

- Alkner & Tesch, 2004 Eur J Appl Physiol 93(3):294-305

- Narici et al. (2020) Eur J Appl Physiol (e-pub ahed of print)

- Kyle et al (2003). Nutrition 20(3):255-60

- Garcia-Pallares et al. (2009) J Sports Sci Med 8(4):622-8.

- Blocquiaux et al (2020). Experimental Gerontology 133