Hi there. Welcome to post 55 of Strength & Conditioning For Therapists and the second part exploring blood flow restriction training (BFR). Last week we covered the basics – what it was and how to do it. Today we’re going to look at the evidence, specifically: blood flow restriction training in rehabilitation and we’ll also look at the contraindications.

What is Blood Flow Restriction Training

As a recap, BFR training involves reducing arterial blood flow to, and preventing the venous return from an exercising muscle by means of a pressure cuff (or elastic wrap) placed proximally on the muscle. It creates a hypoxic environment, effects other changes and the consequences mean that you can induce significant strength – and hypertrophic – gains using very low load, in fact as little as 20-30% of 1RM

Can We Use Blood Flow Restriction Training In Rehabilitation?

We discussed last week that because the loading is so low that this has a clear appeal in a clinical environment whereby performing high load resistance training might not be advocated or indeed possible. So, can we do this and is there any evidence that it works?

Short answer, yes. If you survey the MSK literature, you find the application of BFR in populations including: knee osteoarthritis, ligament injuries, and people susceptible to sarcopenia. Let’s flag up a few of the many studies here.

BFR and Knee OA

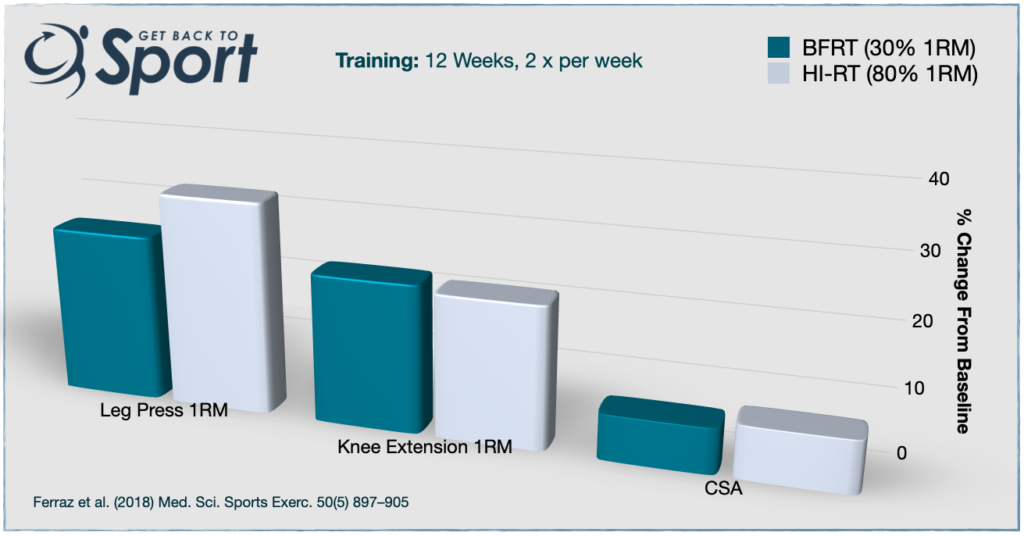

Ferraz et al (2018) evaluated the effects of 12 weeks of twice-weekly resistance training in women diagnosed with knee OA randomly assigned to one of 3 conditions: Low intensity resistance training at 30% 1RM; Low intensity resistance training at 30% 1RM with BFR (BFRT in figure below) and; High-intensity resistance training at 80% 1RM (HI-RT in fig below).

The occlusion pressure was 70% of the pressure required for complete blood flow restriction. Interestingly they didn’t use the often cited 30;15;15;15 BFR protocol, participants in the BFRT group performed 4 sets, progressing to 5 by week 5 of 15 repetitions – so in total the same amount of reps per exercise (75), but dosed differently. Also 2 exercises were used: leg press then knee extension, so 150 reps per session. This was the same for the low intensity group with our BFR. The HI-RT performed 4 progressing to 5 sets of 10 reps at 80% 1RM.

I have to say, if it was truly 80% of 1RM, it’d likely be pretty hard to complete 10 consecutive quality reps (I wrote a post on this here). Anyways. so what did they find? I’ve illustrated some of the key findings in the figure below.

Well, the strength gains were significantly greater in the BFRT than the low load group – remember they trained at the same intensity, but with no BFR. By comparison to the HI-RT group, the gains in muscle strength (up to 30%), and CSA, (7-8%) were similar between HI-RT and BFRT. See above.

So it appears, a potential tick for BFR training in OA populations, especially as they reported four of the patients in the HI-RT group were excluded because of exercise-induced knee pain. That does seem a little convenient though doesn’t it…? 😉

Blood Flow Restriction Training in Older Adults

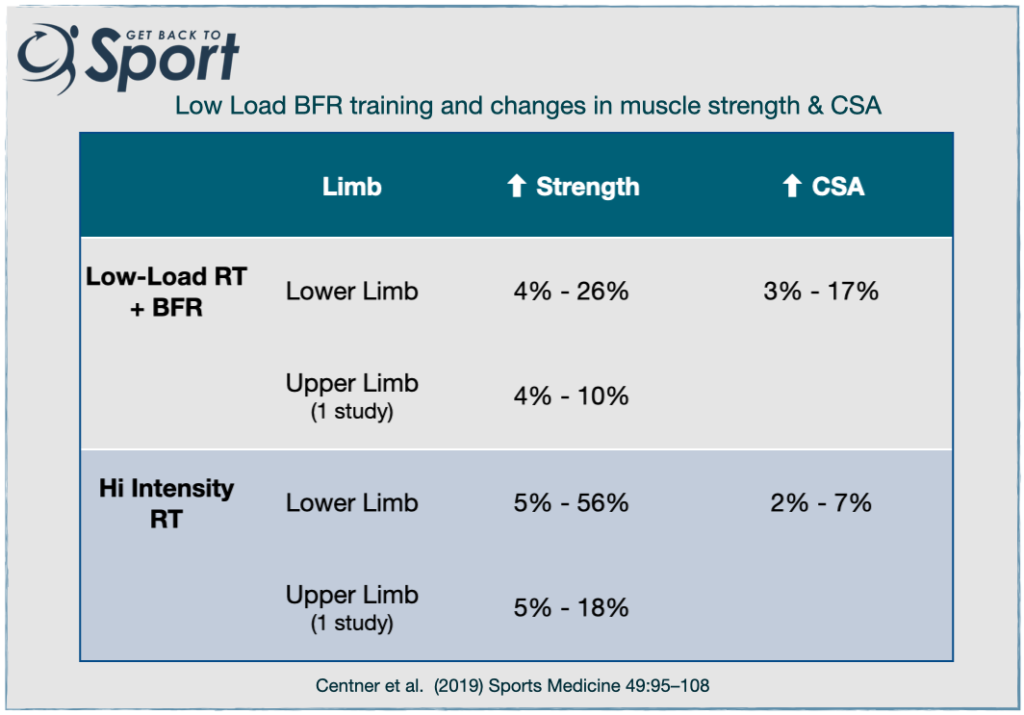

Let’s go to a systematic review here. Centner et al. (2019) were the first to summarise the effects of low load BFR in older adults. 11 quality studies met the inclusion criteria, yielding a population of 238 participants.

The results of their meta analysis concluded that low load BFR was an effective means to increase strength and cross-sectional area in older adults. See the table below for the range of changes observed across the studies reviewed.

This meta-analysis demonstrated that when data are amalgamated across all quality studies in older populations, it appears that In comparison with high-load / high-intensity resistance training, low load BFR training produces comparable changes in muscle mass. However, this is not the case for muscle strength; low load BFR training produces an inferior muscular strength gains compared to high-load resistance training.

Even though the size of effect on muscle strength gains might be inferior with BFR training vs high-load, given the importance of muscle strength to function, perception of pain, dependency and all cause mortality in older age BFR might provide a compelling alternative to traditional RT. This may be especially true where individuals are unable to tolerate heavy loads, or indeed if equipment is lacking. It might be that people can progress from BFR training to traditional resistance training once a good level of strength has been established.

What About Other Applications?

I’m sure you’re sat there thinking of other scenarios where application of BFR could help with rehabilitation. Perhaps post surgery to minimise the loss in muscle strength? See a nice paper by Hughes et al (2019) here (abstract only I’m afraid) and here for a study (Jorgensen et al 2019) to investigate its effects pre total knee replacement (TKR). Studies are now being proposed for post TKR too.

Something that we mustn’t forget are the additional and positive adaptations that we can get from high-load resistance training that are missing, or minimised with very low-loading. These include tendon and bone adaptations. Furthermore, an often cited advantage of BFR training is that it minimises exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD). The adaptations subsequent to EIMD are really important for the remodelling of muscle tissue and the conveyance of increased muscle strength and resilience at long muscle lengths and vulnerable joint positions.

It is for the above reasons, in my opinion, that BFR training should not be used as as standard training tool in healthy populations, athletes and even in older people. It is potentially a very effective tool to use in rehabilitation, for example, where traditional resistance training isn’t possible, or for a short period of time. But we do need to consider progression on from this to ensure opportunities for other important adaptations.

Blood Flow Restriction Training In Rehabilitation

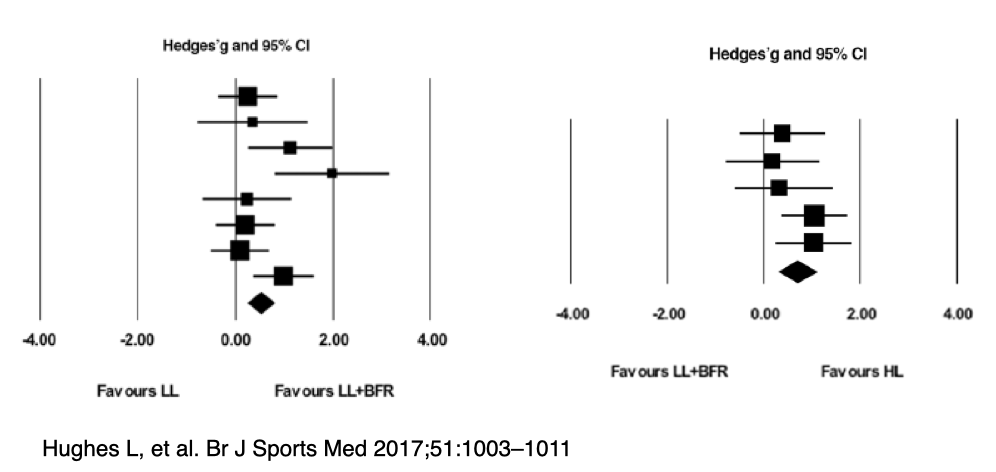

We could continue for ages covering all the different papers here, instead, to succinctly answer the question – ‘is BFR training effective in rehabilitation’, let’s refer to the systematic review and meta analysis by Huges et al. (2017) which attempted to do just that.

20 studies were eligible for review, across a range of clinical conditions. The results indicated that low-load rehabilitative training can be enhanced with BFR , producing greater responses in muscular strength compared with low-load training alone.

You can see below that the effect size for this is 0.52. If you remember from last week, an effect size of 0.52 means that if a similar population were to engage in low-load BFR training, 69% of the population will experience a greater gain in muscular strength compared to low load training alone.

Again, the data shows that strength gains during low load BFR are smaller than those achieved with heavy-load training – again, with a similar effect size.

They conclude low-load BFR training is a more effective alternative to low-load training alone. As I mentioned above they also importantly state that low-load BFR training may be used as a progressive clinical rehabilitation tool in the process of return to heavy-load exercise.

Is Blood Flow Restriction Training Safe?

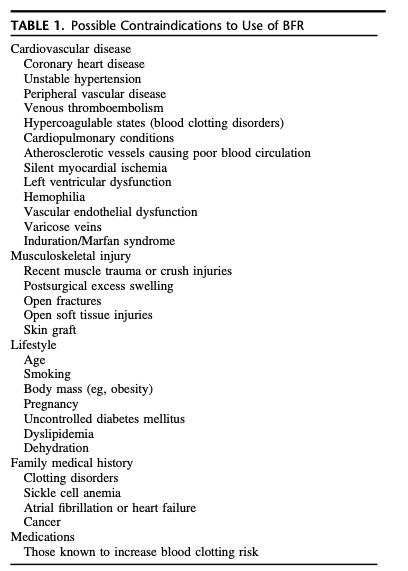

Finally, what about safety? BFR is generally well tolerated and safe for most individuals. Search the literature and you can find all manner of papers. However, we do need to be careful in certain populations, such as those with hypertension and some patient groups, like those who have undergone orthopaedic surgery. The reason being, there may be a heightened risk of adverse events.

Often, techniques like ensuring a wide enough cuff and lower occlusion pressures can mitigate some of the risks. A full review on the safety considerations of BFR is beyond the scope of this post, but I would refer you to a paper by Brandner et al (2019) for a good discussion on the topic. You can access the paper here and below is their useful table on the contraindications

Summary

So, what’s the consensus, is BRF training useful in rehabilitation? I would say yes. That said, we need to pay close attention to the patients and populations with whom we use it to avoid unnecessary risks and of course use an individualised approach, both to the rationale, and the protocol for deployment. It’s good tool for the box; low-load BFR training can provide a more effective approach to low-load and more tolerable approach to heavy-load rehabilitation

Sign up to my mailing list below to be the fist to hear of new online & in-person course listings