Hi there and welcome to post 68 in the S&C For Therapists series. In this post we’re going to expand on the previous post that explored the evidence base of increased mortality risk associated with muscle weakness. Specifically we’ll be looking into resistance training and mortality risk and trying to understand if by engaging in strength training can we impact the increased mortality risk associated with muscle weakness.

What is Resistance Training?

Okay, so there are a few things to note before we get into this. As you can probably predict, there are a multitude of different approaches to evaluating the relationship between resistance training and mortality risk. Let’s take the description of the interventions; these range from ‘strength training’, ‘resistance training’, ‘weight lifting’ etc. you get the idea. Also, because we need to evaluate resistance training behaviour on mortality risk over a long period of time, the evaluation of ‘amount’ of exercise performed is based mainly on self-report and it’s retrospective. So, we’re reliant on individuals both accurately remembering and reporting their previous behaviour, often recalling over many years.

Because of these limitations, it’s virtually impossible to obtain an accurate measure of anything apart from frequency or duration of resistance training behaviour, and even then it has its limitations. We can’t really comment on intensity, and we’re struggling to ascertain an accurate measure of dose (intensity plus sets, reps etc).

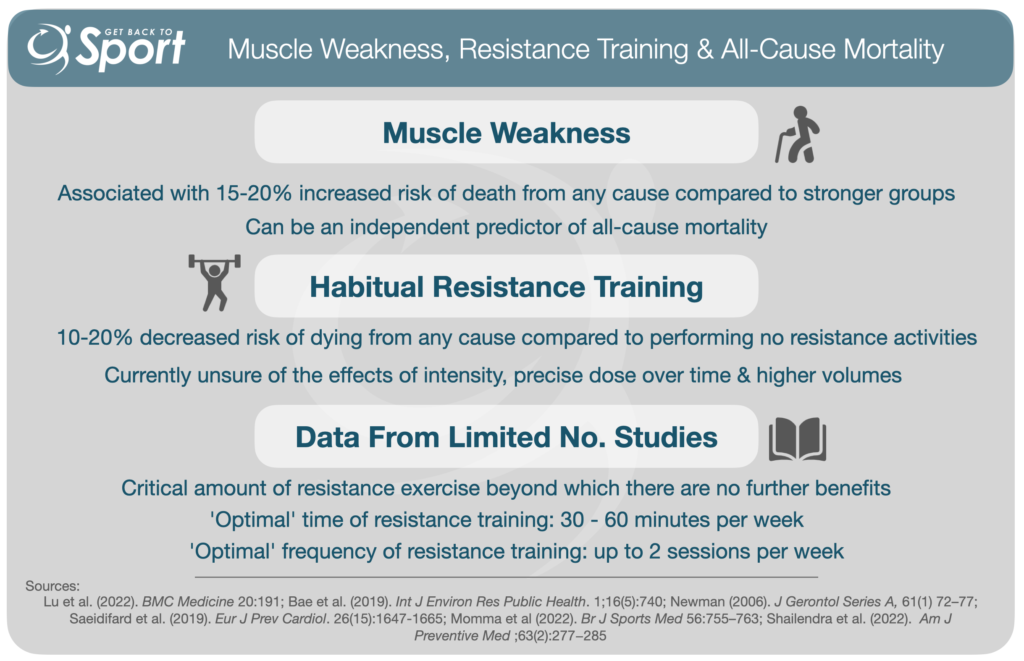

That being said, if we have sufficient population numbers, it is a worthwhile exercise to evaluate if self-reported habitual resistance training behaviour has an impact on mortality risk, especially given that muscle weakness can convey a 15-25% increased risk of death from any cause compared to those who are stronger.

All Cause Mortality & Resistance Training

A good place to start is with recent systematic reviews and meta analyses. Is the body of research sufficiently large to conduct a systematic review, and if so, what are the results.

So, there are several systematic reviews on this topic. Here we’re going to look at 3 recent SR in chronological order.

A systematic review of (n= 11) studies published up to 2017 (342,820 people) by Saeidifard et al. (2019) found that performing any amount of resistance training was associated with 21% lower risk of all-cause mortality than doing none. Interestingly, further analyses revealed that performing >0 to 2 sessions of resistance training per week was associated with lower all-cause mortality, but doing more than two sessions of resistance training was not.

When resistance training activities were combined with moderate to vigorous physical activity the risk of all-cause mortality reduced even further – a 40% risk reduction compared to those not performing either activity.

“Any amount of resistance training was associated with 21% lower risk of all-cause mortality than doing none“

Saeidifard et al. (2019)

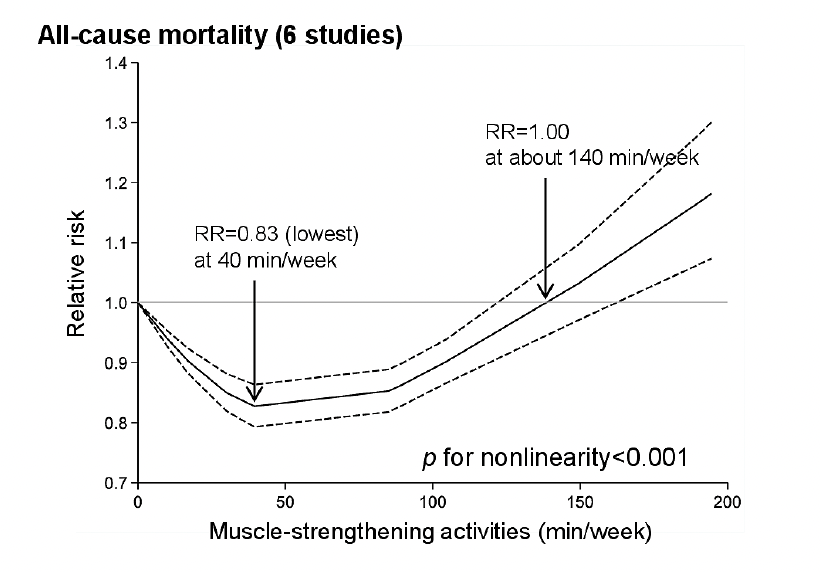

In a further attempt to qualify the optimal dose of resistance training on disease and dying, Momma et al’s. (2022) meta analysis of data from n = 16 studies revealed a 10-17% risk reduction in all cause mortality and non-communicable disease.

Further analysis of studies that provided sufficient information (n = 4), revealed that the maximal risk reduction (10-20%) was observed at approximately 30-60 minutes of resistance training activities per week (see below).

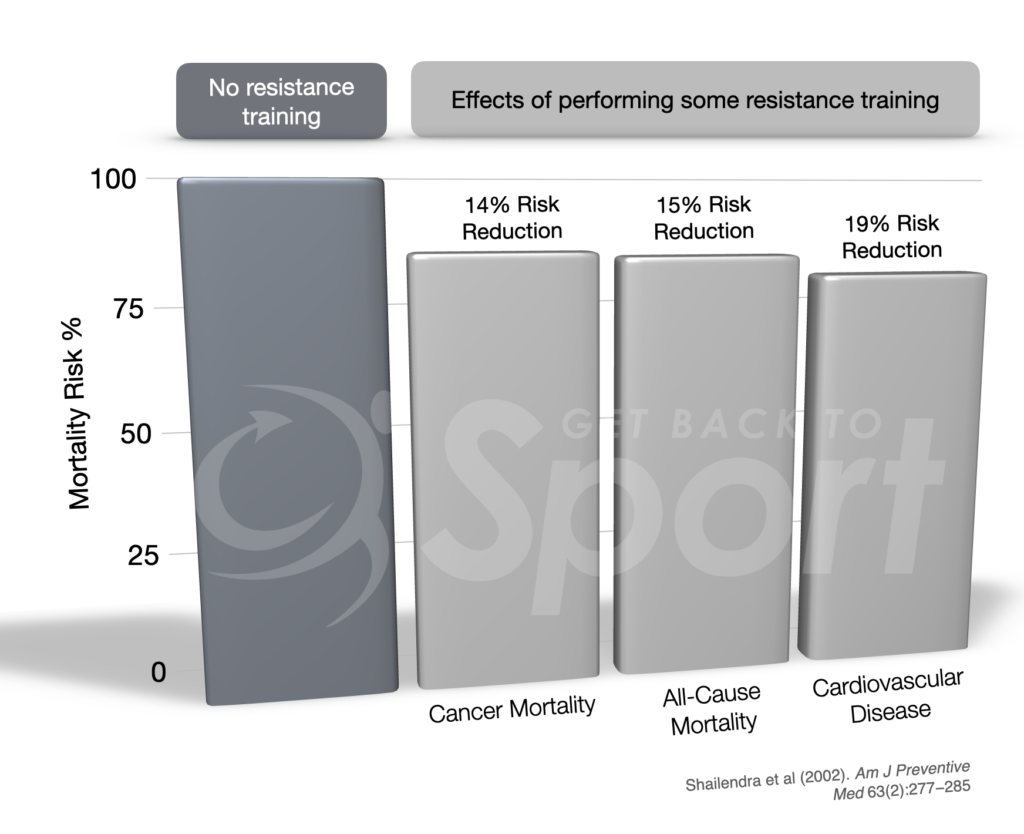

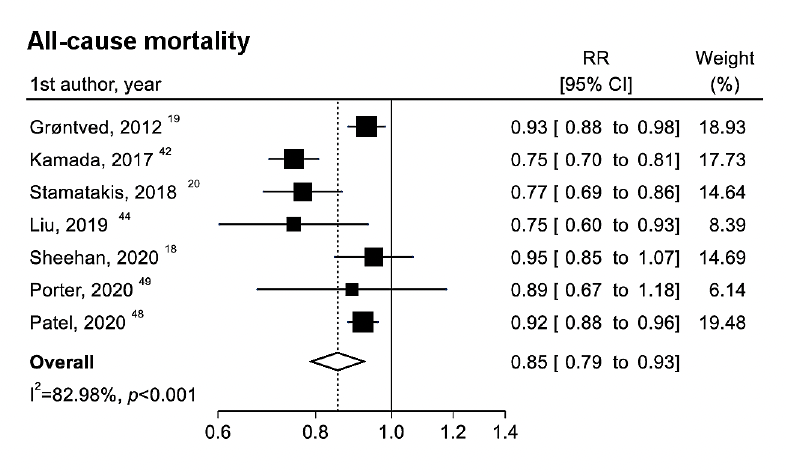

Finally, and with a similar aim to Momma et al, Shailendra et al. (2022) performed a systematic review and meta analysis, and 10 studies met their inclusion criteria. Compared with undertaking no resistance training, undertaking any amount of resistance training reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 15% (RR [RR: relative risk see here and below for what this is] of 6 studies=0.85; 95% CI=0.77, 0.93), cardiovascular disease mortality by 19% (RR of 4 studies=0.81; 95% CI=0.66, 1.00), and cancer mortality by 14% (RR of 5 studies=0.86; 95% CI=0.78, 0.95). See below:

Does Resistance Training Influence Mortality Risk?

So where does all of this leave us? I think we can conclude that habitual resistance training is a good thing 😉 Self-reported habitual resistance training of any amount is associated with a a reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality compared to performing none.

This is also true of non-communicable disease; self-reported habitual resistance training was associated with a reduction in risk of suffering from cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

A hazard ratio (HR) can be considered as an estimate of relative risk, which is the risk of an event (or of developing a disease) relative to exposure. Relative risk (RR) is a ratio of the probability of the event occurring in the exposed group versus the control (non-exposed) group.

What About Dose?

At present, we don’t have solid data on the best prescription, that is to say we can’t conclude anything about intensity, but we are able to make some inference about frequency. It appears that there may be a critical amount of resistance exercise beyond which there are no further benefits. This has been estimated to be approximately 30 – 60 minutes per week when measured in time (Momma et al. 2022) or up to 2 sessions per week as estimated in frequency (Saeidifard et al. 2019).

We do need to view this with caution, however. For example, mortality risk reductions diminished at higher volumes than 60 minutes per week of resistance training was based on only 4 studies.

Also to note, if we add in moderate to vigorous physical activity, mortality risk reductions may be diminished even further compared to performing neither of those activities.

What are the Mechanisms?

So, why does resistance training seem to convey a reduction in risk of dying?

As we said last time, higher functional capabilities are associated with greater strength, particularly in those who have lower baseline strength levels. Resistance training is also associated with improvements in lean muscle mass, which is important for function, but also for things like metabolism. Clinical exercise studies have shown that resistance training has favourable associations with glucose and lipid metabolism, regulating insulin sensitivity, blood pressure and the reduction of visceral fat, all of which are associated with a lower risk of mortality.

Summary

Taken together with part 1 here is what we know:

As always, thanks for reading. Please feel free to share.

Go further and integrate this into your practice

REFERENCES

- Momma et al. (2022). Muscle-strengthening activities are associated with lower risk and mortality in major non-communicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Sports Med; 56:755–763

- Saeidifard et al. (2019). The association of resistance training with mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 26(15):1647-1665. Abst

- Shailendra et al. (2022) Resistance Training and Mortality Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Preventive Med; 63(2):277−285.