I’m pleased to continue answering the questions asked of me on Twitter on S&C with reference to rehabilitation. This is the 3rd week, so if you haven’t seen the previous posts on The Principles of Training and The Misunderstanding of Muscle Strength, click here to check them out. This week we’re looking at PERIODISATION and rehabilitation.

I’ll be continuing this weekly for many more weeks to come as there is plenty to cover! If you have a question on S&C that you’d like to ask, and in particular if you work in the rehab world please Tweet me @Claire_Minshull

So this week we’re looking at PERIODISATION. Many thanks to the many therapists including @Raisin_Girl; @BevacquaNicolas and @WLCPhysio for raising this important topic! . Questions ranged from both ends of the spectrum :

- “What is periodisation” To

- “How to structure a linear or non-linear periodization programme within the rehabilitation context?”

So, quite a bit to cover.

What Is Periodisation?

Let’s start with the basics. Periodisation is basically the division of a large training period (termed macrocycle) into smaller blocks (called mesocycles). With respect to sports performance, periodisation offers a framework for manipulating training prescription to achieve a planned and systematic change in focus and load that ultimately culminates with an athlete achieving peak performance at the most important competition of that cycle, or year. [1,2] (For Olympic athletes this is a 4 year cycle and requires considerable planning!)

To exemplify, high-level performance in most sports requires high-level performance across several discrete areas. Team sports players need to possess good agility, straight line speed, cardiovascular fitness and muscle strength and power. For track and field athletes this list may be shorter, but nevertheless it will still include multiple different components. To achieve adaptation in all areas requires a systematic and planned approach; one that permits optimal adaptation to training and that avoids maladaptation, or interference and breakdown. [3].

Periodisation In Rehabilitation

Clearly in most rehabilitation settings, it’s not a case of pure performance optimisation, there’s a rehabilitative element. But we can, and should, view periodisation as an important tool within rehabilitation settings. Regardless of whether or not your patient is an athlete, most will need to make often quite substantial improvements across a range of indices, and I think it’s here where periodisation is of most use to physiotherapists. If we think of the macrocycle as the whole rehabilitation programme, we can then develop different mesocycles to target specific outcomes throughout that programme. Attempting to condition everything all at once risks overburdening the neuromuscular system, and the patient.

Just a note here, there are several ways in which to periodise within a conditioning programme: linear, non-linear, blocked… and you can even apply this to one specific element of performance/function to optimise adaptation across a year. However, as I explained above unless you’re in high-performance sport, I think utility of periodisation within physiotherapy settings is in managing a multitude of different rehabilitation outcome requirements within a single recovery programme.

Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve discussed honing the specificity of your intervention and then how to deliver on specific rehabilitation outcomes using muscle strength as an example. Clearly and as I said earlier, as a therapist you’re often in the situation where you need the patient to make improvements over multiple parameters. These can include muscle strength, muscle power, sensori-motor performance, cardiovascular ‘fitness’ and then if you have the luxury of seeing the patient for long enough, tailoring the programme to the meet patient’s performance goals. This is where the concept of periodisation can help.

Establishing the Hierarchy of Importance

What’s most important? From a sports perspective, we need to understand the demands of the patient’s sport; for non-sporting patients, similarly we need an understanding of the physical demands of the patients’ goals and in both conditions we need to have an estimate of what’s required to build resilience against future injury and breakdown.

Once we’ve done this, we can then establish a hierarchy of importance of which factors are most important at what stage of the rehabilitation process and then ensure the full programme is designed to achieve this, i.e. construct the mesocycles.

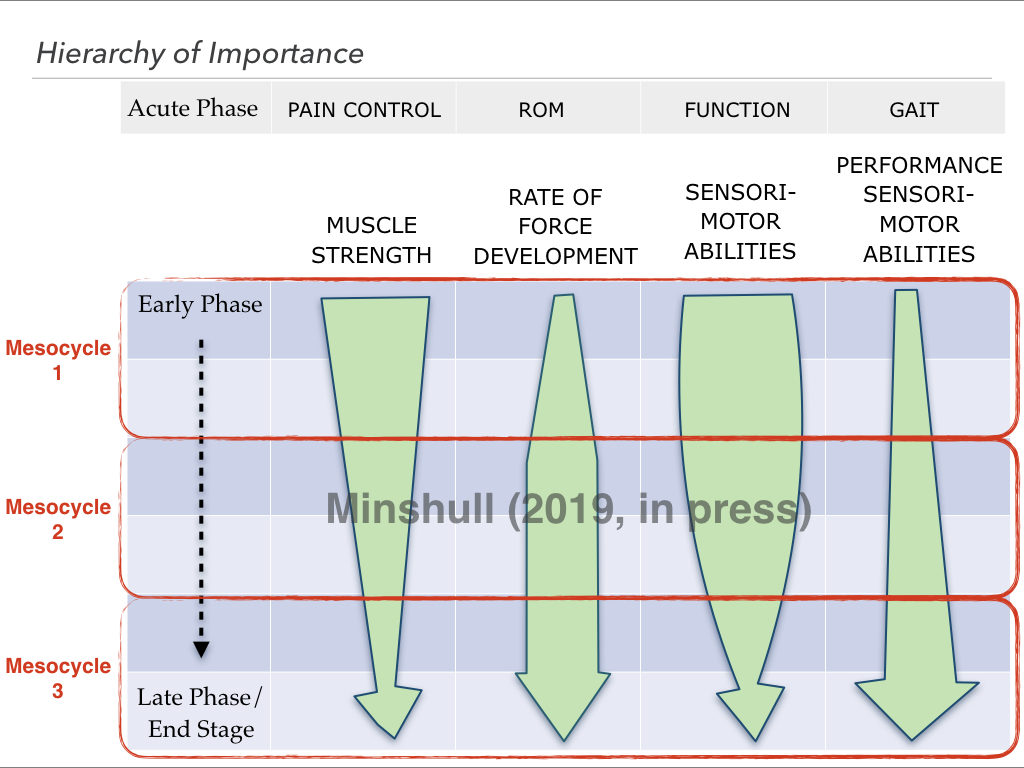

I put together this figure below to illustrate the basic concept of periodisation within rehabilitation[4]. Whilst different surgeries, patient populations and goals will each require a specific approach, this should form a template from which you can work from.

Let’s assume this is a 6-month rehab programme, for ACLR (yes, arguments are for longer, but NHS models are even stretched to offer this), or TKR, pick your condition. And we’re assuming that that ROM, pain and restoration of gait have already been addressed in the acute post-operative phase. We now have 4 specific parameters that we need to work on:

- Muscle Strength,

- Rate of Force Development (RFD), or muscle power

- Sensori-motor Performance (Proprioception)

- Performance-based Sensori-motor Performance (drills tailored to patient’s end goal)

See in the figure the red box: Mesocycle 1, that first mesocycle represents here the first 4-weeks of this 12-week hypothetical programme. During the rationalisation of what’s most important we’ve the determined the principal focus in the early stages of rehabilitation is development of strength and sensorimotor abilities. We can now construct two 4-week progressive programmes of the right dose and intensity to enhance performance on each of these elements. As we discussed in the post on the Principles of Training, clearly one set of exercises will not magically improve both elements!

Moving into the next 4-week mesocycle (Mesocycle 2), we’re still focussing on strength development and sensorimotor abilities, but we gradually start to focus more on explosive force production (muscle power, or rate of force development). Finally culminating in Mesocycle 3 with the principal focus being performance-sensorimotor abilities and rate of force development. Here, dynamic exercises would represent the sports-specific demands and threats if this patient was an athlete. By the time we reach the final stages of the rehabilitation programme, or macrocycle, the athlete will have achieved the required foundations in strength, explosive force production and ‘static’ sensorimotor performance deemed necessary to return to play. Likewise, with the knee TKR patient it is the aim that they will have sufficient strength, power and proprioceptive acuity to e.g. walk their dog on unstable ground with minimal pain.

Progression Between Mesocycles

This is a framework that can be adapted and changed commensurate with different patient profiles and required elements of function/performance. What’s really important is to establish during the planning phase the markers patients need to achieve to permit them to progress to the next cycle, or phase of rehabilitation. For example, how much strength improvement do they need to make, what improvements in balance and control are you looking for, and so on.

Take Home..?

In summary, you can get as complicated and detailed as you like with this, but unless you work in high performance sport (which I know some of you do 🙂 ), all likelihood is that you don’t have the time to work with patients until they’re at their peak performance, and also, It’s likely someone else’s remit at that stage anyway.

Keep things simple, work out what elements of performance/function your patients need to improve, rank them in order of importance and then look at how much time you have with them. Then construct a plan; break down your macrocycle into smaller more manageable mesocycles to address the most important needs first, ensuring sufficient time on the chosen elements to ensure physiologic adaptation. That’s it, simples!

[retweet]

IT’S HERE! Download your Free 14-page guide: Strength & Conditioning for Therapists

References:

1. Brown & Greenwood (2005). Periodisation essentials and innovation in resistance training protocols. J Athl Training 42;367-373

2. Fleck (1999). Periodized strength training; A critical review J Strength Cond Res 13:82-89

3. Maughan & Gleeson (2004). Adaptation to training in: The Biochemical Basis of Sports Performance. Oxford University Press pp191-221

4. Minshull C (2019). Conditioning Efficacy; A Road Map for Optimising Outcomes in Performance-Based Rehabilitation. In: A Comprehensive Guide to Sports Physiology and Injury Management 1st ed. Porter S, Wilson J (Eds) Elsevier, London UK (In Press)