Image attributes: By Unknown – Giuseppe Ottaviani, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27145755

Welcome to post 31 of Strength & Conditioning for Therapists. Firstly, a quick announcement: this blog will now be moving to bi-weekly posts. Whilst I absolutely love writing these posts and the value that they give (thank you for your lovely e-mails), I want to continue to provide high quality information and practical applications and to be perfectly honest, my time commitments right now are working against me to achieve this on a weekly basis. So, just a minor change – you will now receive my musings of S&C and of how it relates to rehabilitation every other week 🙂 So, back to this week’s post. We’re looking at of muscle strength and ageing…

Strength For Life?

How often do you hear from older people that they’ve been told to ‘reduce their activity’, ‘sit back and relax’, ‘take it easy’? Over the past few years, exercise and the concept ‘exercise is medicine’ has proliferated into medical professions and the medical curriculums (hurrah!). Unfortunately this message still needs to filter into, perhaps the more ‘established’ clinics and surgeries. Last week I met an older client who had been, in effect de-prescribed exercise (if there’s such a thing?) by his GP. He had been advised that to manage the (OA) pain in his knee, he should “do less” [physical exercise] and relax and enjoy his retirement. Whilst there are merits of course in reducing workplace stress and taking up new hobbies etc. I’m not so sure taking exercise off the table is such a wise approach. In isolation you may say, ‘yeah well, I don’t know the facts, medical history etc.’ but when I tell you this chap was in his early 60s, overweight, 1-year of (worsening) OA-related knee pain, was previously active and no reported contraindications to exercise… you can likely hear the sigh reverberating throughout my entire body and soul.

Okay, even if there was a good medical reason for this patient to think carefully about the exercise choices he made (which it appears there wasn’t), whether intended or not, the use of language by the respected medical practitioner in this case removed exercise as a treatment option in the patent’s mind, and likely a habitual daily activity. I think we’re pretty convinced that exercise, even walking regularly, has far reaching health benefits, for both quality and quantity of life. Anyways, I digress a little.

Given that we’re S&C focussed here, let’s evaluate the topic of muscle strength and ageing.

Old People Are Fragile, We Shouldn’t Load Them

I get the fear here; when you see someone who looks weak and fragile, the last thing you want to do is get them to lift something heavy, right? “What if if break them?” 😉 Well, let’s consider this from the opposite perspective.

What happens when you unload a system, for example immobilise a limb with a plastercast, enforce a prolonged period of bed rest due to illness, send people to space where there’s no gravity….?

Indeed, the neuromuscular system adapts to the decreasing demand placed on it. No longer are the muscles required to support a joint, enable locomotion, or the bones to support the body against a gravitational load. Now reconsider this scenario and replace the astronaut with an older person. Are they suffering any similar effects? I’m sure we could list a few, like:

- Sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle strength, size & quality)

- Arthrogenic inhibition of, for example. age-related degenerative knee/hip pain on muscle strength

- Decreased engagement in physical activity associated with age

- Decreased engagement in physical activity driven by knee pain

In the examples where an acute event, like limb immobilisation following fracture, there is (or should be) a standardised approach to reconditioning that limb. But in the older person…well not only is there a complete lack of a standardised approach to maintaining physical conditioning, as illustrated above, some medics might even advocate the opposite. Gulp!

Muscle Strength and Ageing: Is Strength Important In Older Age?

Let’s take a quick look at the literature. Obviously this section could be an entire doctoral thesis in length, but for the purpose of this post, I just want to highlight a couple of things.

1. Muscle Strength & Knee Pain

We know that age-related MSK conditions such as osteoarthritis are huge societal and economic problems – throughout the world and it’s typically the symptoms of pain that cause people to seek treatment, disengage from physical activity and that drives absenteeism. So does muscle strength, or muscle weakness, have any bearing here; is muscle strength/weakness related to knee pain?

A cross-sectional study by Muraki et al. (2015), sought to clarify the association of quadriceps muscle strength with knee pain using a large-scale, population-based cohort. The sample involved 2152 men and women (mean age 71.6 ± 12.2 yrs) with knee osteoarthritis (OA) and they obtained assessments of quadriceps muscle strength, strength relative to body mass (BM), muscle mass and grip strength from each participant.

Analyses revealed that quadriceps muscle strength and strength relative to BM were significantly associated with knee pain, after adjustment for age and body mass index, and this was independent of radiographic knee OA. Interestingly, however, no associations were observed with knee pain and grip strength or muscle mass of the lower limbs.

Meaning? One interpretation is that quadriceps muscle strength may have a more important role in the experience of knee pain (or not) compared to muscle volume i.e. the weaker you are, the more likely you are to experience greater knee pain, regardless of your thigh cross-sectional area. And, whilst grip strength is often used a s a proxy marker for strength, it’s probably not the best in this setting.

Is that the full picture though??

I recently had a interesting discussion with an MSK Physio from Australia, whereby we were discussing that there’s almost certainly a bi-directional element to this relationship: is it that weakness that leads to more pain initially, or is it that pain leads to more weakness due to disengagement in activities etc. He brought this paper by Kemnitz et al (2017) to my attention.

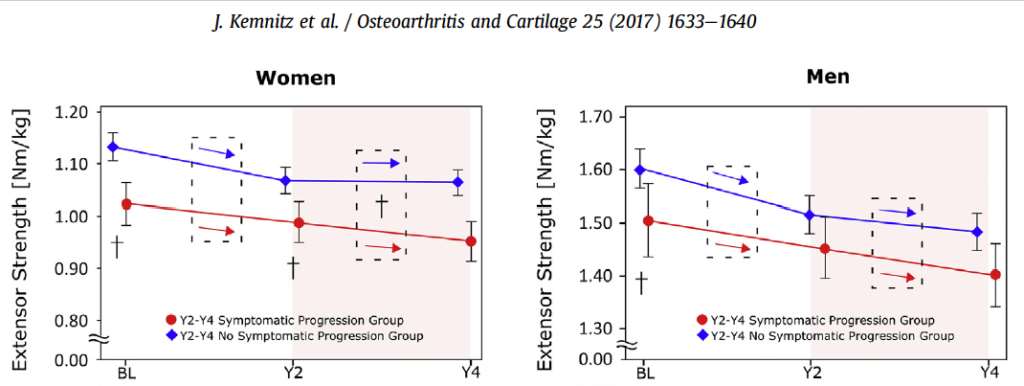

The authors here aimed to ascertain the extent of relative strength loss on symptoms of OA – prospectively, which is neat! This means that rather than taking a group of individuals with OA and measuring their muscle strength and symptoms of pain in a single time point (as in the Muraki paper mentioned above), they recruited a group of men and women with radiographic OA, assessed them at baseline and then assessed them again at 2 years and 4 years. Specifically alongside muscle strength, they monitored the symptomatic and radiographic progression of OA.

The authors found no statistically significant relationship between the longitudinal change (loss) in muscle strength and the symptomatic or radiographic progression of knee OA. So on first glance it appears as though the loss of thigh muscle strength might not be related to knee OA pain. However, take a look at the figure below, especially the women’s data. Do you notice how much stronger the non-symptomatic progression group are at baseline (blue line)? I.e. those women who didn’t experience any progression in knee pain were stronger at baseline, and at all time points thereafter.

Indeed, if you read further into the paper, the authors’ analyses reveal that the absolute knee extensor and flexor strength at baseline (men and women) and Y2 (in women only) was associated with a subsequent symptomatic progression of OA. This means, lower levels of strength at baseline in men and women was associated with the progression of knee pain by the next assessment point.

So, it’s probably inaccurate to say that muscle strength has no bearing on knee pain, more likely (and in my opinion) it’s related to the absolute level of strength relative to body mass (among other things). I’ve often discussed how interesting it would be to gather sufficient data to determine if there’s an ‘optimal’ strength to body mass ratio that would offer the best attenuation of symptoms of OA. Now there’s a study to undertake if you’ve got the will and resources!

2. Muscle Strength & All-Cause Mortality

So muscle strength (or weakness) is associated with OA knee pain, which as we know is an age-related condition (predominantly), but is that it?

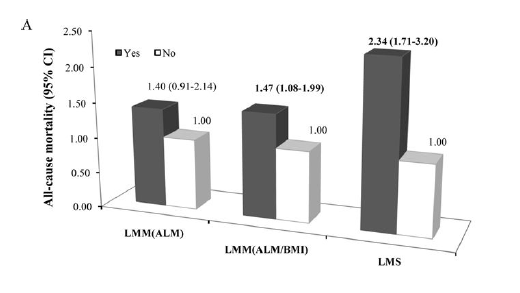

Li et al. (2018) aimed to prospectively examine individual or joint associations between low muscle mass and, or muscle strength and all-cause mortality among a very large sample of US older adults (N = 4449). Mortality is also another – ahem – (predominantly) age-related event, so it makes sense to look at this too.

Low muscle strength was independently associated with elevated risk of all- cause mortality, regardless of muscle mass, MetS and sedentary time among US older adults (N = 4449). See the 3rd from the right (dark) column in the figure below. LMS = low muscle strength LMM = Low muscle mass.

[Quartiles of measurements of knee extensor strength were calculated & the lowest 25% was designated as low muscle strength]

Low muscle strength was strongly associated with all-cause mortality; the Odds Ratio (3rd column above) is 2.34, (95% CI 1.71–3.20), which means the odds of dying from any cause were 2.34 times greater in individuals with weak thigh muscles compared to those with stronger thigh muscles… suggesting, that muscle strength may be more important than muscle mass in predicting ageing-related health outcomes in older adults.

Low muscle strength is more strongly and significantly associated with all-cause mortality than low muscle mass; yet another high quality study to indicate the greater importance of strength versus muscle cross-sectional area/muscle mass. Indeed those individuals in the subgroup with low muscle mass had significantly increased risk for all-cause mortality only when they also had low muscle strength.

Summary

So this is just a snapshot of the data, and you could argue that I’m biased, after all I do write a blog on strength and conditioning 😉 I’m yet to find any studies that show that frailty and weakness have no bearing on quality of life and that exercise in older populations, when delivered properly and adhered to, fail to deliver positive health-related outcomes. I do think, on balance, there’s sufficient evidence to soundly put the statement to bed that we need to put our feet up when we get older, especially these days when we lead a far more sedentary life than previous generations, and I’m pretty convinced that we should go further and adopt a proactive approach to combatting sarcopenia

HAVEN’T GOT IT YET? Download your FREE 14-PAGE GUIDE: Strength & Conditioning for Therapists

References

- Muraki et al (2015). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16:305

- Kemnitz et al (2017) Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 25 1633 -1640

- Li et al. (2018) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 50(3): 458–467.